Clinical Consult | Overview

Pediatric sleep problems, though highly prevalent, tend to be under-diagnosed in the primary care setting. Beyond the infant and toddler years, many parents don’t think to mention sleep disturbances during visits, and time constraints may prevent PCPs from inquiring. A 2010 study of children 0 to 18 years in a large primary care network found that only 3.7 percent had an ICD-9 diagnosis of a sleep disorder, much lower than the prevalence suggested by epidemiologic studies. Snoring alone, for example, has a reported prevalence as high as 27 percent, while insomnia is as high as 5 to 20 percent.

Sleep problems may only come to clinical attention if parents note that the child snores or has other clear evidence of sleep-disordered breathing. In practice, however, clinicians should consider asking about disordered sleep when children have difficulty concentrating or changes in academic performance, behavior or mood. The history should include questions about snoring and breathing during sleep, daytime sleepiness, sleep hygiene, and the child’s sleep schedule.

Sleep disorders by age

Behavioral sleep disorders predominate in early childhood: difficulty in falling and staying asleep without a parent being present, for example, or difficulties setting and enforcing limits around bedtime routines and behaviors.

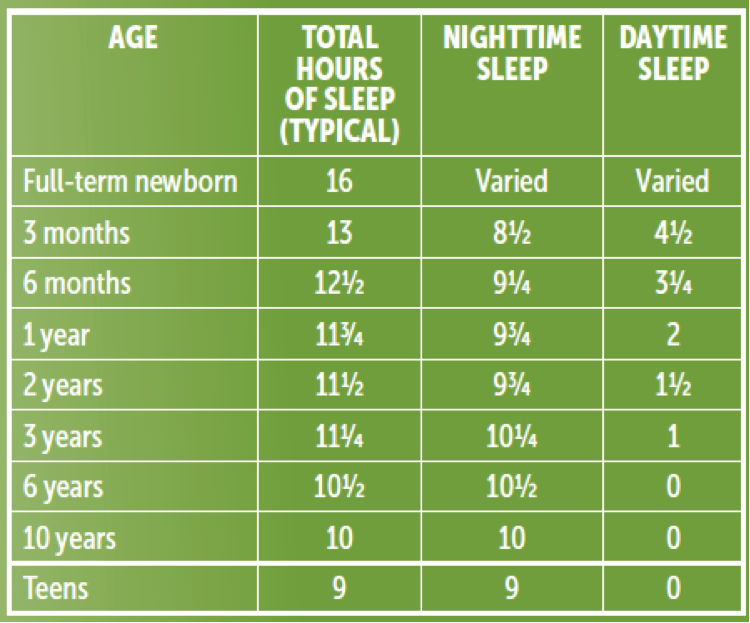

These can be addressed with behavioral interventions, such as a consistent bedtime routine, leaving the room while a child is still awake, and introducing schedule modifications including a regular schedule for naps and nighttime sleep. With older children, a reward system for preferred sleep behaviors can be effective. Sometimes parents expect young children to sleep for unrealistic lengths of time (see chart). In cases such as these, setting a later bedtime — when the child is truly sleepy — can prove effective.

In older children, the most common problem is insufficient sleep. The majority of teens get fewer than the recommended 8.5 to nine hours because of poor sleep hygiene, playing computer games, and texting close to bedtime (activities that rev up the brain). Many teens develop circadian phase delays, staying up late on weeknights and even later on weekends (coupled with sleeping several hours beyond their usual wake-up time), leaving them significantly jet-lagged when Monday morning rolls around.

Sleep-disordered breathing

Sleep-disordered breathing, mostly commonly obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), peaks at ages 3 to 6, when the tonsils and adenoids are at their largest size relative to the upper airway, and then again during adolescence, often concurrent with overweight and obesity.

The prevalence of OSA is up to 4 percent in all children and even higher in children who have low muscle tone, craniofacial abnormalities, neuromuscular disorders, certain chromosomal variantsm, or who are obese. Common signs and symptoms of OSA include snoring, witnessed pauses in breathing, gasping, or snorting, and mouth breathing. Night sweats, sleeping with the neck hyperextended and reemergence of bedwetting (due to increased nighttime urine production) also can be signs of OSA.

OSA leads to fragmented sleep and is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness in older children. Younger children tend to present more commonly with symptoms of attentional deficit or hyperactivity. An estimated 25 percent of children with ADHD have OSA, and the attention and behavioral symptoms often improve after the OSA is treated.

When there is clinical concern for OSA, an overnight sleep study is the diagnostic gold standard. The first line of therapy for OSA is usually removal of the tonsils and adenoids. Nasal steroids such as montelukast are sometimes used as well in milder cases.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), if the child can tolerate it, is usually the next treatment choice for OSA, and it can dramatically improve daytime symptoms. CPAP, too, is palliative rather than curative. The optimal pressure settings can change over time, requiring adjustments. Other treatment options include orthodontic interventions such as maxillary expansion, and weight loss as a long-term strategy.

Other, less common medical causes of disordered sleep include restless legs syndrome and narcolepsy.